| Description: | Select Guide Rating

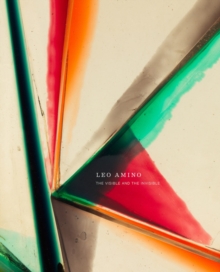

A beautifully produced celebration of Leo Amino’s sculptural adventures in light and color, richly complicating the story of abstraction in America The first monograph to be published featuring the work of the Japanese American artist, Leo Amino: The Visible and the Invisible introduces a vital revision into both the canon of 20th-century avant-garde sculpture and the history of Asian American art.

The volume is published in association with the first significant museum exhibition dedicated to the artist’s work since 1985, Leo Amino: Work with Material at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, and shares a title with the artist’s first solo exhibition in New York since 1973, held at David Zwirner Gallery in 2020. Edited and written by the artist''s grandchild, poet and curator Genji Amino, the book includes additional texts by a selection of writers, poets and scholars including Aruna D''Souza, Wayne Koestenbaum, Lucy Lippard, Susette Min, Neferti Tadiar, Mary Whitten, Ronaldo Wilson and Karen Yamashita. Richly illustrated with images from the BMC Museum and Zwirner exhibitions, the volume includes an extended chronology featuring never-before-seen archival images and ephemera from across the artist’s career.

Amino is the first artist in the United States to take up plastics as a principal material of sculptural composition, the innovator of cast plastics in American sculpture, and the most represented artist of color in the history of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s annual exhibitions for sculpture after Isamu Noguchi. He is the only Asian American artist to teach on faculty in the history of the Summer Art Sessions at Black Mountain College, where he taught alongside artists including Josef and Anni Albers, Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, and informed the education of students Ruth Asawa, Kenneth Noland and Harry Seidler, among others. Recommended to the faculty at Cooper Union by Josef Albers, Amino taught there for 25 years, introducing students such as Jack Whitten to sculptural concerns.

Across a breadth of media and compositional approaches often remarked during the artist’s lifetime for its inventiveness and versatility, Amino’s oeuvre brings into focus the dynamics of perception, articulating space, light and color through the optics of encounter, interpenetration and absorption. Almost exclusively self-taught, Amino drew on three months’ training in direct carving technique at the American Artists School in Greenwich Village in order to adapt the study of form latent in wood grain into a promiscuous and autodidactic material investigation. Beginning in the early 1940s, the artist’s experiments in new media emerged from his dissatisfaction with painting on the sculptured surface. In 1945, Amino became the first American sculptor to employ cast plastics in an exploration of the question of interior and exterior relation through the problem of integral color, introducing the newly declassified military and industrial material of polyester resin into a history of media experiment following the Plexiglas works of Bauhaus and constructivist artists László Moholy-Nagy and Naum Gabo. Amino envisioned a mode of sculpture for which the principal means of composition would be light and color as early as 1949, anticipating the concerns of the next generation’s Minimalist and Light and Space movements whose artists would take up his medium of choice two decades later. In 1965, Amino made the decision to abandon his other avenues of inquiry in order to dedicate himself exclusively to the new material, beginning a series of geometric, refractional compositions in resin that he would pursue until his passing in 1989.

Born in Taiwan under the auspices of Japanese colonial rule and educated in Tokyo, Leo Amino (1911–89) immigrated to the West Coast as a young man in 1929, where he attended San Mateo Junior College before anti-Japanese sentiment moved him to cross the country to New York in 1935. During the second Sino-Japanese and World Wars, he found himself an outsider to both Japanese and American nationalisms, signing an anti-fascist declaration by Japanese American artists in New York City in 1941, and ultimately resolving never to return to Japan. Rather than approaching the New York School of painters and sculptors who came to represent Abstract Expressionism as an exceptionally American phenomenon, Amino embraced a community of outsiders, finding a measure of freedom among the exiles and refugees of Black Mountain only two years after the college’s integration. Joining Noguchi, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and others in denouncing fascism in Japan while attempting to carve out a space for their work on the East Coast of the United States during the era of Japanese American incarceration, he is one of few artists of Asian descent in the first half of the 20th century to have figured so prominently in the art historical record.

|